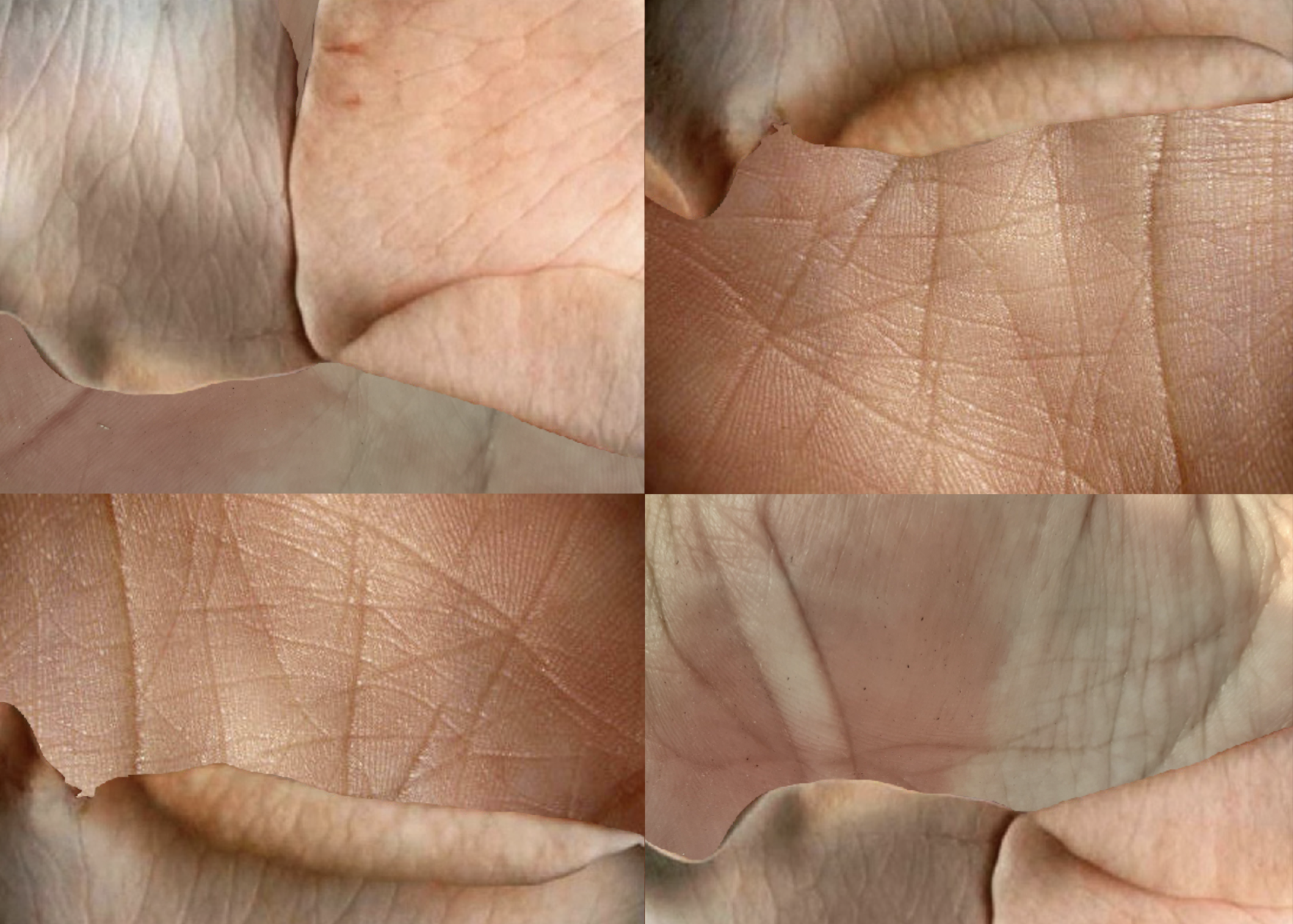

Cos Ahmet’s biome focuses on the skin, its many functions and manifold appearances. Starting from his own skin, Cos reflects on the largest human organ – an organ which embodies and protects a life system, namely the body. While the skin has always been populated by bacteria and thus functions as a life system in itself, the pandemic is transforming it into a much-feared zone.

We are increasingly threatened by the sweat that passes through its pores and the microbes it may share. In light of the current situation, we recall the history of touch, in particular the centuries-old convention of the handshake – a tactile encounter between two human beings, expressing mutual respect and the intention of not harming each other. This very ritual is now shunned; touch is being avoided for the risk of possible contagion. By zooming into the skin, Cos points at the vulnerability of the life system that it exposes. He asks us to reflect on the consequences of touch, the meeting of one skin and another. The risk of being harmed stands next to the possibility of harming others, aggressivity next to involuntary injury.

Yet, there is another sensation emanating from the coloured photographs, a feeling that works subtly against these negative, pandemic-led associations. The close-ups stimulate haptic viewing. As readers, we’re gently touching the surface of the tracing paper with the eyes. The offer of contact made by the work points to the emotional warmth that touching can imply. Exposing one’s skin to another signifies openness, an interest in connection and exchange with other bodies. Cos emphasises this function of the skin when bringing different skins in contact with each other. In his biome, hairy skin meets hairless skin, human skin is touched by nonhuman skin.

When turning the pages, the reader’s skin touches another skin – the skin of the paper. Permeable to liquids of all kinds, paper is as porous as skin. It absorbs fat, dirt and colour, and it tears if not treated with care. If touched wrongly, it cuts into the skin of the reader, thus mirroring the ambivalence inherent in human skin. As a site of creative expression, Cos’s biome also demonstrates the function of skin as a carrier of inscriptions. Alongside papyrus, it was animal skin on which letters were engraved in ancient times, and in many cultures, skin is still used for mark making, whether for political, social or aesthetic purposes.

Skin, however, is never a blank sheet – it is always culturally and politically coded. Whether through colour, texture or surface structure, skin triggers assumptions about the life system that it epitomises. It speaks about race and cultural identity, religion, privilege and work. Often times, skin serves as a marker – it situates us in time and in space. Wrinkles indicate age, skin colour suggests geographic origin. Frequently, these assumptions are misguided, resulting from deeply entrenched prejudices. If we understand skin as a text, it’s probably told by an unreliable narrator. We can never be sure about the clues that it seems to give us. We don’t know where it came to life and if it has been consciously or unconsciously altered. Cos makes this uncertainty a central element of his work. In view of his biome, we are unable to picture the being that lives through and with the skin represented here. Knowing about its relation to the artist’s body, we may situate it in the Western world, and we may suppose that it’s young rather than old. But we cannot confirm that these assumptions are true.

Looking at the close-up photographs, we cannot even be certain that the skin depicted belongs to a human being. Partly covered with a silver gloss, partly consisting of flaps of skin sewn together, the images trigger questions about the boundaries between humans and nonhumans. What are the features of human skin, and where does it meet its nonhuman counterpart? How far are human and nonhuman skin entangled, defying possible distinctions from the outset? What’s the role of the artist in this context, and what does this say about the creation of life systems? On the page, we find no definite answers to these questions. Cos’s biome provides multiple pores for entry and exit, and it encompasses many layers of skin – each of them suggesting another response. Touch it, let it touch you, and you’ll surely find out more about the life system that we call skin.

About Enzyme 2: Thinking of the periodical as part of an intellectual work of digestion, artists Jorgge Menna Barreto and Joélson Buggilla proposed Enzyme magazine for their Liverpool Biennial commission project. Artists Cos Ahmet, Abbie Bradshaw and Linda Jane James, along with curator Sarah Kristin Happersberger, were invited to collaborate on Enzyme 2, that would become the Life Systems issue. Each worked on a biome relating to the theme of systems – bodily, environmental and social. ‘Life Systems’ became a meeting point to connect their practices, share ideas, harvest and feed. Each artist produced a section of the magazine, and translated their contribution into a two-hour online Life Systems public event under the banner of ‘Digesting Life Systems Lecture Series’.

Jorgge Menna Barreto, Ph.D. (b. 1970, Araçatuba, Brazil) is an artist and educator whose practice and research has been dedicated to site-specific art for over 20 years. Menna Barreto approaches site-specificity from a critical and South American perspective, having taught, lectured, and written extensively on the subject; he has participated in multiple art residencies, projects and exhibitions worldwide.

Sarah Kristin Happersberger , (b. Heppenheim, Germany) is a researcher and curator based in Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Happersberger has a background in art history and specialises in time-based art, socially engaged art and collaborative practices. Happersberger was invited as a guest editor for Enzyme 2: Life Systems, a durational project by Jorgge Menna Barreto and Joélson Buggilla, with collaborating artists: Cos Ahmet, Abbie Bradshaw, Linda Jane James, Bonnie Ora Sherk and Newton Harrison, commissioned for 11th Edition Liverpool Biennial 2021: The Stomach & The Port, curated by Manuela Moscoso, 19 May - 21 June 2021.

Images: EH-pih-DER-mis by Cos Ahmet. Skin Biome, depicting human / non-human skins printed on translucent vellum. Article Photo: Bia Braz. Enzyme 2: Life Systems, made in collaboration with Jorgge Manna Barreto and Joélson Buggilla, was presented at the 11th Edition of Liverpool Biennial 2021, The Stomach & The Port, curated by Manuela Moscoso.